The following is from the response of The Machine Zone Community Interest Company‘s response in January 2018 to the Department of Culture, Media and Sports final consultation prior to decisions about FOBT stakes and othe rgambling related issues such as advertising.

For relative brevity, we here comment analytically on aspects of connected issues. A few representative sources of evidence are cited but it is assumed that previous consultation evidence is familiar.

While there has been a great deal of attention from many individuals and sectors to B2 machines, it is usually implicitly understood that Fixed Odds Betting Terminals cannot be seen in isolation but figure in complex relationships with the rest of the gambling and betting landscape. Whether terms of reference allow or not, the FOBT debate has become an ongoing discussion about gambling as a whole, particularly about all electronic gambling machines, digital devices and online gambling, gambling promotion, gambling harm, regulation and control versus business and personal freedom, and so on.

One important reason that FOBT gambling relates to the wider field is that many of the features of FOBT machines and their availability are common across gambling devices. We believe that much is to be learned from the research into FOBTs for applying to other areas. In any case, like many people with an interest in the issues, we implicitly identify FOBTs with concerning aspects of the present and developing gambling and betting industries.

EVIDENCE

The term ‘evidence-based’ when attached as a modifier to policy or practice has become part of the lexicon of academics, policy people, practitioners and even client groups. Yet such glib terms can obscure the sometimes only-limited role that evidence can, does, or even should, play.

http://www.ruru.ac.uk/pdf/Rhetoric%20to%20reality%20NF.pdf

While we recognise the crucial role of evidence, we see the term as problematic.

- Evidence gathering includes access to data, and this is by no means complete.

- It is unrealistic to expect many responding to the consultation to engage at a level deemed by terms of reference as ‘evidential’ or ‘analytic’. This raises the question of methodologies of evidence seeking, and more importantly, the basic assumptions, values, attitudes and orientations unerlying the evidence-seeking process. One aspect of this is that a hierarchy of evidence may pertain with quantative, statistical, academic discourses dominating rather than being part of the process. There is a lack of good qualitative research. Most concern about electronic gambling machines arises from user experiences yet this is perhaps written off as ‘merely’ anecdotal. This should be a prime research focus. Nancy Dow Schull who spent 13 years on site in Las Vegas looking at gambling behaviour and machine design argued that there is a need for in depth inte rviews etc to provide evidence impossible to collect quantitatively (Nancy Dow Schull, Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas). We recognise necessary caution in looking at evidence from other cultures and environments but nevertheless beieve there is much to be learned, particularly from Australian research. In particular, to date there has been at best only very scant phenomenological/anthropological research at the sitse of gambling practice. Clearly there are many difficulties to such an approach, but this simply signals the possibility that research to date is far from complete in arriving at adequate understandings and much more needs to be done in the future.

- With regard to the present enquiry/consultation, there is no agreed or well formulated definition of what counts as evidence. Who will analyse and interpret a wide range of submission based on ‘evidence’; what basis will such analysis and interpretation be taken upon, with what expertise, peer review, avoidance of preconceived ideas etc?

Often, calls for evidence in politics are rhetorical. Look out for calls for ‘robust evidence’ or ‘rigorous evidence’, phrases used by committees, indivudaul parliamentarians, interest groups, industry. As noted above, there will be different understandings of what sort of evidence is appropriate. This is not peculiar to the FOBT consultation process. For instance, many educational charities boast solid evidence bases, yet when they are examined, it is found that this conceals more than it reveals; in ‘gambling education’ in school aged students, the complexities are often ignored and the ‘evidence’ is spurious or based on very limited ambitions.

- ‘Evidence based policy’ has become a government mantra in recent decades. It has also become a subject to be researched in academic and professional contexts, as well as internally in parliament. It is certainly not ‘transparent’ although claims based around it implicitly or explicitly attach unwarranted authority. Very many policies stemming from evidence based research and consultations have proved to be ingenuous, wrong and dangerous. We believe too, with the Goldsmith Fair Game (2013) report, that in any case, government policy is not decided by evidence alone.

- Confusion around, and rhetorical usage of ‘evidence’, leads to competing narratives. For instance, from the BMJ:

http://jech.bmj.com/content/early/2017/09/29/jech-2017-209710

- As with tobacco, the deleterious harmful effects of FOBT gambling were discovered not by academics but by human consequences. (It was insurance actuaries who made the links in the case of tobacco). There has been a countless number of individual stories of the dreadful consequences following use of electronic gambling machines. Since research is lacking, and since a great stigma around gambling addiction prevails so that the number of people ‘going public’ is small, we may legitimately assume that the actual human consequences are unseen across populations. Bankruptcy, mental health problems, relationship breakdown, suicide may be attributed to other factors than gambling to ‘protect’ reputation.

- Underlying values led to liberalisation of gambling by the Labour government. Some of these values pertain today. These values include, partly, a dependence upon growth in the sector for tax revenues. There are also libertarian values around personal freedom, minimal state intervention, and light-touch regulation. Central to the values which generate policy and research is the commitment to business freedom.

We believe that the deleterious impact of modern gambling is a public health issue. We think that gambling should be treated every bit as stringently as alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs. The underlying values of welfare and health protection need promotion. This will lead to a rearrangement of foci in evidence seeking.

CONTEXTS

- The digital revolution has taken everyone by surprise. All aspects of society are affected. In every sector, adaptation and future orientation are challenging. In the case of the gambling and betting industries, adoption of digital products seems ‘ahead of the game’. This is coupled with legal and regulatory liberalisation, and associated responses from public, government, regulators, researchers and public health.

We are concerned that in examining the content and discourses of relevant political and regulatory bodies in terms of the current debate, responses and forward planning seem to be reactive. Further, there seems to be a dominant narrative of future monitoring, postponement of core policy and an expectation that the gambling and betting industries will develop as they will, and the preferred response is to take ‘action’ upon singular cases of excess (such as FOBTs).

We would prefer to hear a much stronger sounding set of policies and strategies for the future, which demonstrate awareness of, and set out proposals to tackle, the growing problems associated with gambling and betting.

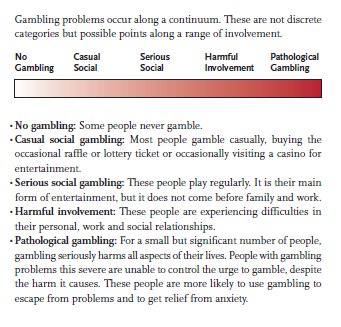

- While weight is properly given to business freedom, personal choice and responsibility and economic factors, the public health approach to problem gambling seems unduly relegated as of lesser importance.

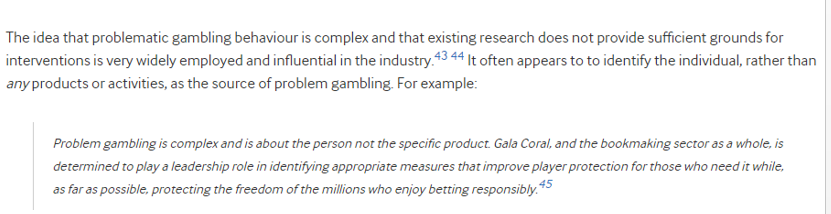

- It is probably the dominant narrative in public thinking that ‘addicts’ are responsible for their plight, and/or ‘addicts can/should receive treatment. Although the present process of consultation examines other factors such as machine design, convenience and accessibility, clustering, our analysis suggests that such factors do not presently receive sufficient attention, and that their is undue and unhelpful focus upon the ‘pathology’ of the individual.

- The acronym RET (research, education and treatment) is frequently mentioned as a monolith, hence the acronym, and we understand this block signifies various important and potent approaches to minimising ‘problem gambling’. We say more about RET below, but point out here that the random lumping together of three highly important and distinct areas both minimises their importance by becoming a passing reference and acts to reinforce the diversion of attention from the contexts of machine design, promotion, marketing, convenience and accessibility, cross-industry corporatism etc.

- There is a strong public distaste for the harms done by FOBTs. This has translated into an equally strong distaste for all gambling with the Gambling Commission reporting that 23% of the public believing it would be better if gambling were banned altogether. http://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/survey-data/Gambling-participation-in-2016-behaviour-awareness-and-attitudes.pdf

‘ADDICTION’

Sometimes called addiction, problem gambling, pathological gambling. An objection is that such terms summon up negative stereotypes. What is certainly true is that they delineate the individual subject. The player, gambler, person becomes the sole bearer of ‘something wrong’. As the Goldsmith Report (Fair Game, 2012) claims:

By categorising a small minority of people as

‘problem gamblers’, the state and the industry are

able to continue to promote gambling as a safe

and legitimate form of leisure and entertainment

for the ‘normal’ majority. Images of problem gamblers

in our data are many. They include those

labelled as losers, weirdos or simply those who

don’t gamble well, but most are flattened out and

decontextualised accounts of problematic people.

Industry’s views of problem gamblers, in particular,

are often deterministic and derogatory. They are

seen as people who are unable to control their behaviour.

Some described treatment as a waste of

money, and people with gambling problems as

‘problem people’.

Problem gamblers are problem people. They

are drug addicts, criminals, they are unable to

control their impulses and this is why it is impossible

and pointless trying to prevent them from harming themselves.

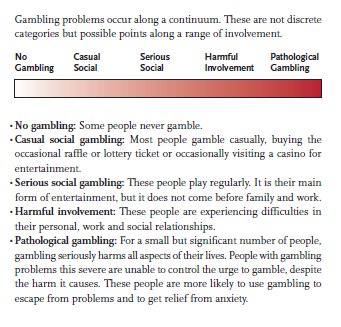

Much research, acknowledging this reservation, sees ‘addiction’ as occurring on a continuum. While the results of gambling may be severe for those with a problem, those around them and society at large, the compulsion to gamble is better seen in terms of strength so that an individual may at some times resist, at other times be overwhelmed. This is important because environmental cues obviously are key to eliciting responses, attenuating inhibitory power. A visual representation of ‘problem gambling’ such as that below suggests that there are largely ignored populations who are at great risk, and individuals who can move between levels.

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, 2005

We suggest that conceptualising gambling behaviour on such a spectrum alerts us more precisely to the scale of gambling harms with different intensities, and prevents us from imagining that ‘the problem’ is with a minority population of pathological gamblers.

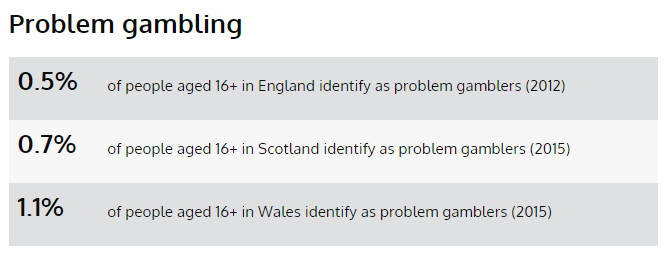

Yet dominant narratives, certainly from the industry, continue to emphasise that levels of harm are very low, and that those who suffer are ‘ill’ (and would suffer whatever forms of gambling and betting are available). The percentage of the population cited as ‘pathogical gamblers’ hovers around 1% in the UK although this disguises variations. In Northern Ireland, for instace, the figure is quoted as 2.3%.

The industry and others say that these figures are stable over time. This suggests that many years of research, education and treatment have had little or no effect in tackling the ‘problem of problem gambling’.

More seriously, the figures quoted refer to the national adult populations. Yet:

Industry apologists argue that no more that 1 or 2 percent of the population meets the diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling, with perhaps 3 or 4 percent qualifying for the less severe “problem gambling.” But, as Schüll points out, those figures are for the general population. “The percentage of pathological and problem gamblers among the gambling population is a good deal higher, and higher still among regular(or “repeat”) gamblers—20 percent, by some estimates.”

As the APPG’s consultations showed, there is much evidence that a very high number from this revised figure are characterised as multiply disdvantaged, and betting companies appear to cluster their premises where the most vulnerable live.

PUBLIC HEALTH

Even if one accepted the 1% figure as meaningful, one has to factor in the number of people affected such as family, economic detriment and health service uptake. As a matter of fact, when some politicians and industry spokespeople talk of the economic implications (tax revenue, profits, employment etc) of curtialing gambling opportunities, these wider costs are often ignored. These factors are well rsearched (with accompanying differences of interpretation) and already figure in the consultation process.

It may, nevertheless, be instructive to compare ‘problem gambling’ rates with other mental health disorders, using the more conservative figures.

Problem gambling 1-3%

Bipolar 1 1%

Schizophrenia 1.1%

Alcohol Dependence (England) 1.4%

We suggest that major mental health disorders are not all treated equally in terms of research, priority and treatment. The connotative weight of ‘addiction’ may play a part but it seems ironic that with so much focus on the ‘pathological individual’, research, the state, the industry, and health services offer much less attention and support to what is clearly a major health issue.

The move to make problem gambling a public health is issue is backed, of course, by the Royal Society for Public Health, may health professionals and researchers. The Royal College of Psychiatrists and the British Medical Association as organisations back the move as do countless doctors.

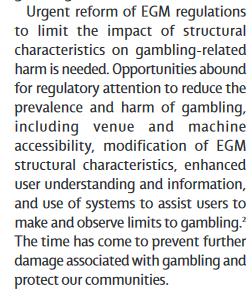

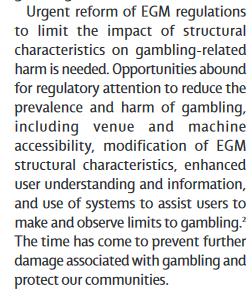

As a public health issue, prevention is seen as crucial to ameliorating gambling harm, and this health strategy involves the full cognisance of the harmful nature of gambling products such as electronic gambling machines. In a piece in The Lancet (January 2018), several researchers argued that

The harms of habitual and disordered gambling are many, and adversely affect individuals, families, employers, and communities. While the development of gambling disorder by players of electronic gambling machines (EGMs) involves complex interactions between multiple factors (eg, decision-making processes, availability of gambling outlets), there is growing recognition of the role of machine design in the progression of the disorder.1,2 We allege that EGMs are intentionally designed with carefully constructed design elements (structural characteristics) that modify fundamental aspects of human decision-making and behaviours, such as classical and operant conditioning, cognitive biases, and dopamine signals.

In other words, the industry exploits human psychological attributes. They conclude:

As a public health issue where we witness threats to health and wellbeing through dangerous products, we expect the same attention to gambling as has been given to tobacco, alcohol and other industries. This entails strong curtailment of specifically identified dangerous products (here electronic gambling machines); the tackling of ‘normalisation’ that follows from promotions, advertising, opportunity and convenience; facilitating independent research with no financial input from industry, this to build on the growing body of research which is highlighting product design, industry strategies, etc.

Public health should not in any way be funded by industries which damage public health. John Catford draws attention to why:

Receiving alcohol and gambling funding is particularly compromising for health and social agencies, sport and fitness organisations, universities and research groups. The time has come for those values-based organizations that already have agreed not to accept funding from Big Tobacco to extend this to Big Booze and Big Bet. And for those who have not done so—to do the same.

- compromise the objectivity and independence of the research and the maintenance of integrity and standards by creating a conflict of interest for researchers;

- foster poor quality or compromised research which may then produce biased and erroneous results favourable to the interests of these industries;

- create a dependence on this form of research funding which may then inhibit other independent research and inquiry;

- reduce the ability of researchers to publish the outcomes of research in reputable, high-quality journals which may have policies which preclude industry-funded research;

- restrict groups from receiving other funding from reputable funding bodies, which will then damage and restrict growth of research performance;

- indicate to the public, professional groups, and government—by associating with these industries—that organization endorses the activities and products of these industries;

- create a more favourable climate for these industries so that regulators will not need to enforce or further restrict the promotion of alcohol and gambling to youth and vulnerable people;

- compromise the organization’s reputation, mission, core commitments and values.

https://academic.oup.com/heapro/article/27/3/307/754330/Battling-Big-Booze-and-Big-Bet-why-we-should-not

As with every aspect of the ‘debate’, however, framing ‘problem gambling’ as a public health issue can make for neat concepts but it is not straightforward and by no means guarantees a significant leap forward (and no more do monolithic concepts such as Research, Education and Treatment).

RESEARCH, EDUCATION AND TRAINING

As noted above ‘RET’ is often bundled into a convenient concept of its own, and often mentioned only in passing.

Or prime concern is that all three areas, each of which is crucial, are too frequently conceived in terms of ‘the pathological individual’.

This reinforces the diversion of attention from the impacts of machine design, environments, convenience and availability, targeting by industry of the mos vulnerable, promotion, marketing and advertising. The reliance upon funding from the gambling and betting industries is no more acceptable than research, education and treatment accepting funding from alcohol and tobacco industries.

There has been a solid output from concerned academics and professionals about how industry funding skews agenda for research. We would wish to see levies and some taxation from the industry ringfenced to contribute to totally independent research initiatives.

Treatment for gambling disorders is woeful, this exacerbated by funding cuts which impac on local authority comissioning services. A much deeper reason for treatment neglect is that, despite its evidentially manifested severity and prevalance, it simply does not figure highly in any government priorities. Ongoing debates about the paucity of mental health services are amplified in the case of gambling disorder.

Education includes campaigns comparable with other public health projects. There is limited evidence that ‘teaching’ players greater awareness about machine features, odds risk etc reduces harmful play in laboratory conditions. Very little evidence suggests that public education has any beneficial effect.

In schools and other educational institutions there is a very chequered history of drugs and alcohol education. These days, such education is seen as part of personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE) but this itself lacks national coherence and delivery. Research has shown what works best in such education. As importantly, it shows what is ineffective or counterproductive: alarmingly such latter education which includes scare tactics, lecturing, talks from ‘recovered’ addicts continues. In the case of gambling education, as in ‘treatment’, there is a low awareness of gambling. However, with state encouragement and initiative, coupled with developments in PSHE, we believe it possible and desirable to include gambling education in state funded education. In whatever case, educational initiatives relating to, or funded by, the industries are unacceptable because the powerful implicit message is that the gambling environment is a safe source of entertainment for the many and that it is the ‘few’ who already have problems who run into danger: as noted above, such messages, combined with that of ‘social responsibility’, may act as good PR for industry, but in any case contriutes to the continuing obfuscation about reality.

FUTURES

FOBT issues are well documented, but internet and app platforms are increasing access to gambling due to the exponential increase in smart phone and tablet computers across Wales. These technological changes are leading to change in social regulation of gambling as a public behaviour, as well as facilitating targeted and unregulated advertising to potentially vulnerable individuals. Trends indicate that these may include older adults and underage children.

An Investigation into the Social Impact of Problem Gambling in Wales (2017) https://pure.southwales.ac.uk/en/publications/an-investigation-of-the-social-impact-of-problem-gambling-in-wales(8b5df31f-4e41-4308-ad28-90617ba9d3ec).html

As we introduced our response, the digital environment has taken us by surprise. There are many opportunities and many dangers. The use of the word ‘exponential’ in the above quotation is precise. FOBTs are just one example of exponential digital gambling growth. Betting shops are beginning to install Self Service Betting Terminals, digital facilities which provide an ‘all in one experience’. Such terminals mirror the micro-environment of the digital phone, tablet or other device. In an increasingly promoted gambling environment, young people especially are at great risk.

Clamping down on FOBTs, reduing maximum stake to £2, adjusting machine designs such as removing ‘replay’ button, lengthening time between bets etc will be of benefit to some users; more importantly it will send out a strong message of intent about the dangers of digital gambling. This should be backed up with what are currently very inadequate areas of research, education and treatment.

There have been many things to learn from the FOBT debates, not least the need to be alert proactively to the future of digital gambling and the need for far more solid bases for regulation and harm prevention across the coming gambling industry’s products.